Our survey asked members of the public to submit records of honey fungus in UK parks and gardens – here are some of the research findings

Summary of survey results

Summary of survey results

We would like to thank all those who participated in the survey on honey fungus. The summary below is an overview of the main findings and has helped us understand where future research should focus.

Participation

The survey provided us with information from 170 suspected cases of honey fungus infection, including photographs in support of 113 cases. The online tools created to help gardeners identify the mushrooms for themselves were highly successful, and 90% of the images submitted correctly showed honey fungus mushrooms.

Only one third of participants created a spore print, so the importance of carrying out this step can be further emphasised. The most common lookalike to honey fungus has a dark spore print, so before panicking over the appearance of clumps of orange-brown mushrooms gardeners ought to check the spore colour.

Signs of disease

We wondered how often mushrooms were seen without the presence of disease in a garden, but our findings showed that plant disease had been associated with 90% of cases, the majority of which had plants which were already dead or dying. Mushrooms mainly occurred when a host plant was already dead, and seeing mushrooms on an ailing plant probably indicates that the plant is heavily infected and has extensive root rot.

The most common symptom observed was dieback of the canopy, seen as early defoliation and premature browning, which were observed in four out of five cases. Changes in the production of flowers or fruits and bark symptoms such as bleeding and splitting were each observed in roughly one quarter of cases.

Plant death due to honey fungus infection involves the growth of white mycelium underneath the bark of roots and the stem base, but only one quarter of participants reported seeing this feature. This tells us that the mycelium is probably not easy to spot, and that people are probably not checking under the bark of plants when they die. From this we conclude that there is work to do to educate gardeners to check their dead and dying plants for honey fungus, and supports the value of the RHS gardening advice service for confirming diagnosis of honey fungus in the roots of dead plants by experienced plant pathologists.

Host plants

63 host genera were reported, the most common of which were:

- Prunus (10.3%)

- Betula (8.9%)

- Malus (6.7%)

- Salix (4.6%)

- Viburnum (4%)

- Rosa (4%)

- Juglans (3.5%)

- Acer, Fraxinus & Ligustrum (2.8% each)

The host plants reported were predominantly trees, but smaller shrubs and herbaceous hosts were also listed including anemones, penstemon and fuchshia.

Disease management

Descriptions of disease progression and management approaches revealed that the death of large trees is often not treated according to RHS advice, and dead trees are often cut to a stump and not excavated. As such, the disease was observed to spread along the lines of large roots buried under the garden. Future research will target the role of stumps in the spread of honey fungus in gardens and how best to manage situations where it is unrealistic to remove the entire root system of an infected tree.

Symptoms of honey fungus

Symptoms of honey fungus infection include dieback and death of plants as shown in these photographs.

Survey: what we asked for

-

Find a honey fungus mushroom (or many!)

-

Take photographs showing the top, side and underside of the mushroom

-

Cut off a cap and make a spore print

-

Check that it conforms to the “Quick honey fungus checklist” criteria (see below)

-

Take note of the details of the area in which the mushroom was found including:

♦ The location, as precisely as you can give it (sensitively stored)

♦ How many mushrooms like this are growing together

♦ If it was growing near a plant, if so provide the name of the plant to as greater level of detail as possible and how healthy the plant looks

♦ If there are other similar mushrooms growing elsewhere in the garden/park where this mushroom (or clump) were found. For each new plant with mushrooms please create a new survey entry (answers from each record are locked so the new entries can just be edited instead of started from scratch!)

-

There is a final section to complete only if you have further knowledge about previous incidents of honey fungus in the garden/park. All these fields are optional, but the more information you can provide the better:

♦ Sketch a map of the plants in the area that have and have not been struck with honey fungus in the past and upload this image to the form.

♦ Note any specific details including:

• Distances between plants

• Plant ages

• Soil type

• Aspect

• Slope

• Any steps taken previously to try to manage disease

Quick honey fungus checklist

Quick honey fungus checklist

- Colour honey-beige-brown

- Pale gills

- Pale spore print

- Typically stem of constant thickness along its length (Armillaria gallica can be bulbous)

- Grows in clumps

- Grows near a source of dead or dying (and sometimes apparently healthy) plant material

Honey fungus mushroom identification

Cap – Honey-beige-brown in colour, usually smooth in texture on the upper surface but can be somewhat fluffy.

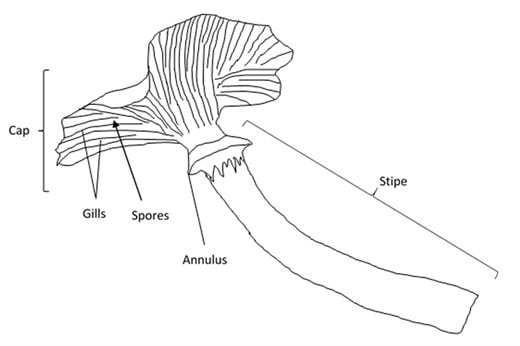

Gills – Membranes running radially across the underside of the cap are the gills, which are pale for honey fungus mushrooms. Some but not all of the gills will run all the way from the cap edge to connect to the central stalk (stipe).

Spores – Spores develop and are released from between the gills. The colour of the spores may be hard to tell while still inside the mushroom cap, but by printing the spores you can observe the colour more easily. Honey fungus mushrooms produce pale (white/cream) spores.

Annulus – A ring of tissue around the stalk (stipe). The species of honey fungus that occur in gardens all have annuli close to where the cap begins, but these can be difficult to spot and may only be present as wispy veils of tissue.

Stipe – The stalk is called the stipe. In most honey fungus mushrooms the stipe is the same width along its length (Armillaria gallica can have a bulbous base). The colour and patterning of the stipe vary, ranging from pale/pinkish/dark brown in colour, and smooth/stripy/scaled in pattern. The stipe is often hollow in the middle.

Growth habits

Honey fungi grow in clumps close to their food source, and only produce mushrooms in the autumn. The fungi feed on plant roots or dead wood buried in the soil. The mushrooms might not appear to be in contact with the stem of the plants they infect, but can be attached to the root system of their host plant or via rhizomorphs even further away.

Once you are sure you have found an incidence of honey fungus, take a look around the wider area to work out which plant the fungi are likely to be feeding from, or if there is no living host but you expect there to be some wood buried in the ground.

Symptoms and signs of disease

When honey fungus infects the roots and root collar of a plant this disrupts the flow of water from being able to reach the above-ground parts of the plant and leaves die back as a result. Also, the season before dieback is observed, a greater-than-usual flourish of flowers or fruit can occur.

Signs that honey fungus is the cause of the dieback include visible white sheets of fungal tissue underneath the bark of thick roots and the base of the stem, as well as the presence of rhizomorphs (aka bootlaces) on and under the bark and in the soil around the root system.